Decision Points by George W. Bush and A Promised Land by Barack Obama

Scattered thoughts on the limitations of presidential memoir

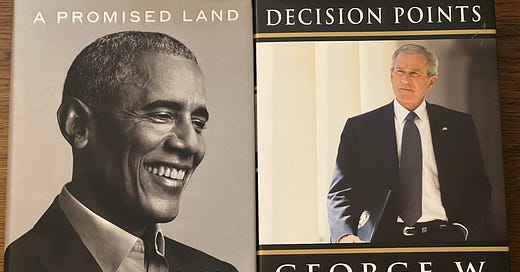

I first read Barack Obama’s A Promised Land (Crown), the first of a planned two-volume set. Immediately, one understands why Obama had this meteoric rise from being an Illinois state senator to, four years later, being elected president of the United States. He is obviously charismatic, intelligent, and thoughtful to a degree that is rare among American politicians. And he is a legitimately good writer. His retelling of how he learned to love reading—going from Ralph Ellison and Langston Hughes to Robert Penn Warren and Dostoyevksy to D. H. Lawrence and Ralph Waldo Emerson (9)—charmed me, I must say. The presidential election in 2008 was my first opportunity to vote. I wrote in Ron Paul—and even had a “Don’t Blame Me, I Wrote In Ron Paul” bumper sticked on the back of my 1987 Ford Ranger—but reading this, I remembered why, even at the time, in my heart of hearts, I thought Obama was the so-called lesser of two evils among the major political parties rather than John McCain. (The Arizona Senator singing about bombing Iran was what did it for me.)

Despite these positives that shine through on most pages, one can see pretty quickly the limitations of presidential memoir as a genre. Obama, as said, is an excellent writer, but too quickly he falls back into speechifying—in the middle of making a point, referencing the American heartland in ways that makes one wonder if he knows he is constitutionally prevented from running for president anymore. And much of this reads as a blow-by-blow account of every element of his administration. In some cases, this works very well—particularly for the, to borrow from our current president, big-freakin’-deal moments, like the response to the financial crisis or the passage of the Affordable Care Act or the killing of Osama bin Laden. The value in such remembrances is self-evident, and Obama’s skillful retelling of such events adds to their value. One does not need, however, the same sort of detail about the Obama administration’s climate efforts—at least this reader didn’t! It made me think, while reading, that a “turning points” approach to presidential memoir may work better.

For all Obama’s thoughtfulness, however, one does not see much in the way of regret over his handling of any particular aspect of his administration. This is not surprising! Modern politics being what it is, people are routinely punished for giving any inch at all. And having to write such massive reflections so few years after living through the period about which one is writing certainly would dampen anyone’s ability to thoughtfully consider mistakes one made. Yet, as a reader, I wanted more. Of course, I was not expecting Obama to side with Republicans—honest disagreement is good! And it is reasonable to blame Republicans more than Obama for the poisonous political climate that emerged during those years. But I still wanted more. Perhaps my expectations were too high. But Tim Alberta, in his excellent American Carnage: On the Front Lines of the Republican Civil War and the Rise of President Trump, makes the point that Republicans were, for political reasons, ready to “play ball” with the president on economic matters—at least until Obama told them, in the middle of debate, “Elections have consequences. And I won.” Was Obama right? Of course! And Republican intransigence was present from the beginning of his administration. But for someone who spoke as if he would bridge the partisan divide, making such an “unforced error,” as Alberta described it, pushed any wavering GOPers firmly into their partisan positions. Obama’s acknowledgements on this front are weak, to say the least. I wanted more.

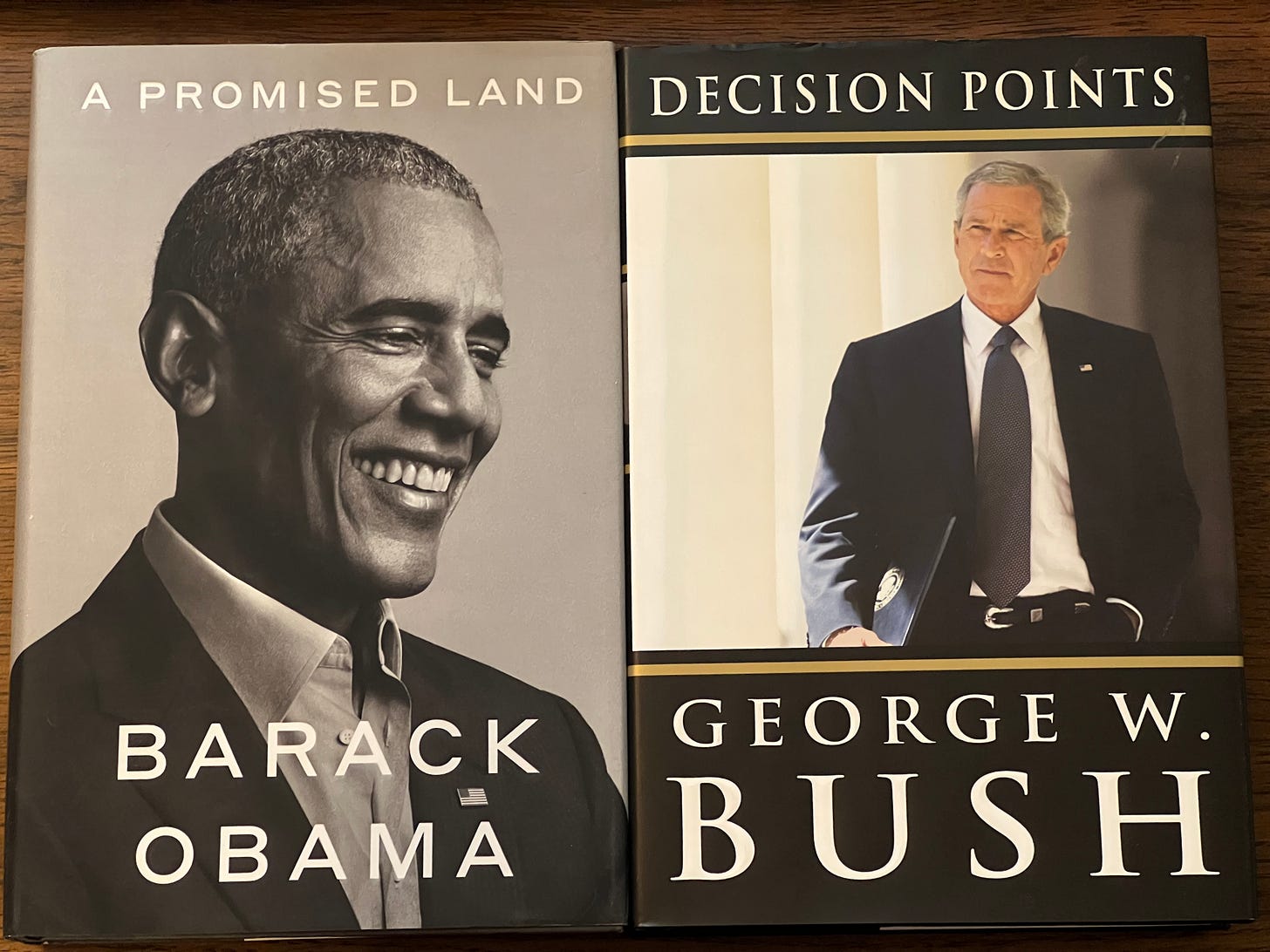

I next read George W. Bush’s Decision Points (Crown). How likely is it that we had back-to-back good presidential writers? Because, contrary to his public image, Bush is a good writer!

Similar to Obama’s memoir, one immediately sees why Bush became the most popular Republican presidential candidate since his father’s election in 1988. (It’s true: Trump in 2020 got 46.9% of the popular vote and 46.2% in 2016, Romney in 2012 got 47.2%, McCain in 2008 got 45.7%, Bush 43 in 2004 got 50.7% and 47.9% in 2000, Dole in 1996 got 40.7%, and Bush 41 in 1992 got 37.4% and 53.4% in 1988.) Bush’s personal charisma leaps off the page. Whatever deficit he had in his public persona, particularly public speaking, was more than made up for in his intense relatability.

He cites Timothy Keller on page 33! I mean, come on!

I also found much of this memoir to be intensely moving, particularly Bush’s discussion of his victory over an addiction to alcohol. Here is how he ends that chapter: “I could not have quite drinking without faith. I also don’t think my faith would be as strong if I hadn’t quit drinking. I believe God helped open my eyes, which were closing because of booze. For that reason, I’ve always felt a special connection to the words of ‘Amazing Grace,’ my favorite hymn: "‘I once was lost, but now am found / was blind, but now I see’” (34).

This speaks to another strength of this memoir: its organization. Rather than telling a straight chronological narrative—which would in all likelihood lead to the kind of blow-by-blow account that I find fairly boring—he organizes his book into themes and events, which he calls “decision points.” This is a far more interesting approach. This allows the author to focus on the overarching narrative, the larger story, rather than getting bogged down in the smaller stories. Now, it did not always work that way—despite the “decision points” framing, Bush’s prose still crept into “this happened, and then this happened” at times. But, on the whole, it is an approach I hope more future presidential memoirs take.

But if I was annoyed by Obama’s unwillingness to take more blame in certain aspects of his administration, I found Bush’s discussion of the War on Terror infuriating. I understand that he is unlikely to come out now and say that the War in Iraq was a mistake, but my goodness—it is almost surely the greatest foreign policy blunder since at least LBJ’s use of the supposed Gulf of Tonkin incident to ramp up American involvement in Vietnam—and this will likely have greater and worse repercussions for years to come. While I’m fairly certain Bush did not “lie” the U.S. into war, using faulty intelligence to rush to war in some hubristic crusade to make the world safe for democracy is almost as bad.

And yet, despite that, I also found myself missing this kind of Republican. Bush clearly had no trouble sticking his head out, politically, if it was something he thought was the right thing to do, whether it was Iraq, Social Security, AIDS in Africa, faith-based initiatives, tax cuts, immigration, or TARP. I disagree with some of this! But it’s refreshing to not have every action come across as poll-tested. We need more sincerity in American politics.