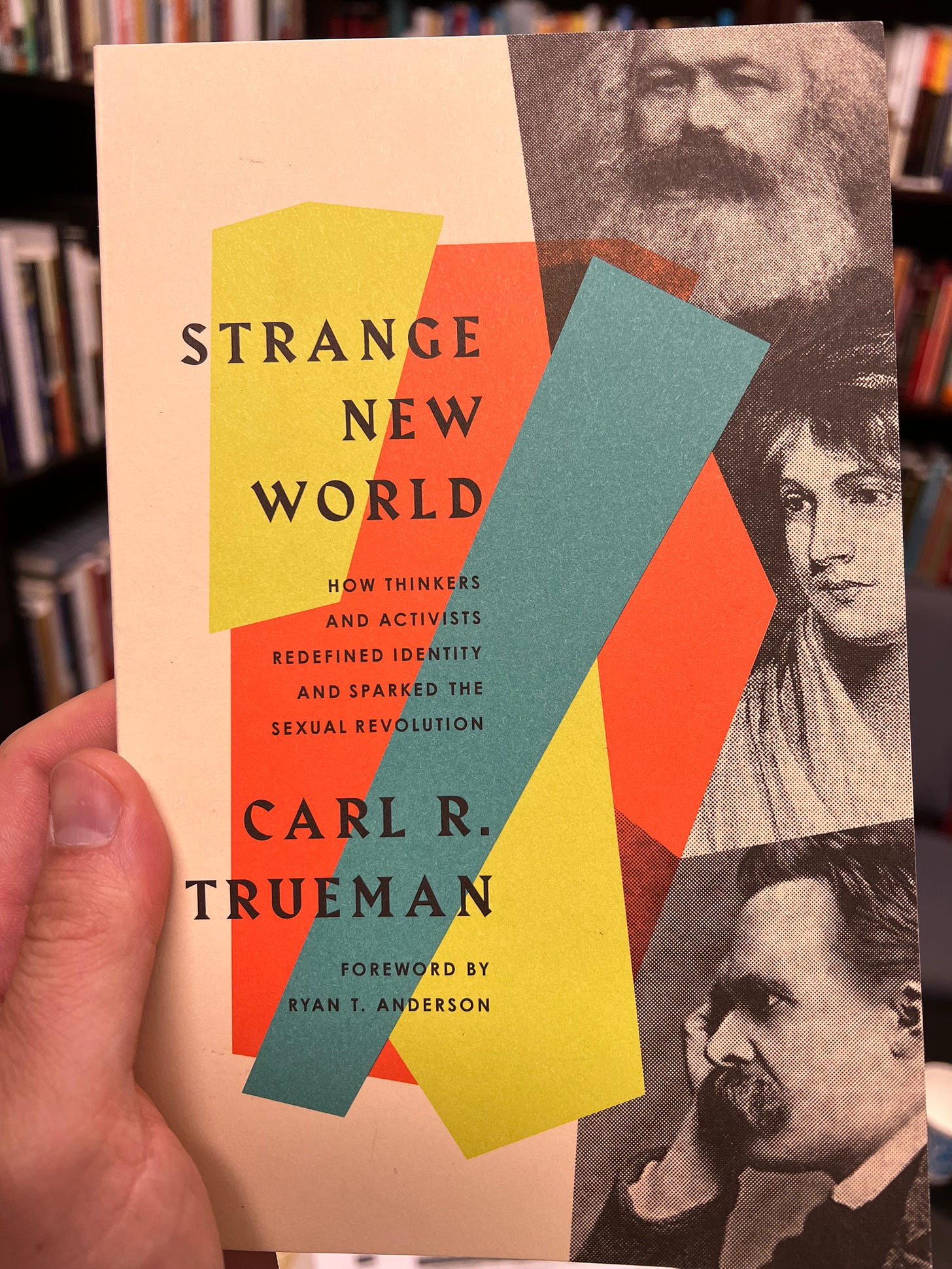

In contemporary American culture, the idea that one can be, for example, “a man trapped in a woman’s body” is an understandable one, something which ought to gain sympathy and help, rather than the scorn and derision previous generations of Americans would have heaped upon such a statement. Carl Trueman’s book, Strange New World: How Thinkers and Activists Redefined Identity and Sparked the Sexual Revolution (Crossway) (a shorter version of his longer and more academic The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self) seeks to discover how this happened. As he writes, “To respond to our times we must first understand our times” (29).

Trueman, a professor at Grove City College, is an intellectual historian, and as such, traces the intellectual lineage of our contemporary way of thinking. How does he do so? How does he think this cultural change happened? It begins with the exaltation of the self: While ancient interrogations of the self almost always directed one outward—one thinks of Augustine’s Confessions, which is remarkable in the ways it reflects the inner life of the author, but always in service of directing him back to God—modern ones almost always turn inward. And this lifting up of the self has happened in tandem with the rise of expressive individualism: Writes Trueman, “the modern self is one where authenticity is achieved by acting outwardly in accordance with one’s inward feelings” (23).

As the modern self was individualized, so, then, was it sexualized—people like Sigmund Freud posited that the self was most authentically expressed when it was expressed sexually. Trueman quotes Freud on this point:

Man’s discovery that sexual (genital) love afforded him the strongest experiences of satisfaction and in fact provided him with the prototype of all happiness, must have suggested to him that he should continue to seek the satisfaction of happiness in his life along the path of sexual relations and that he should make genital eroticism the central point of his life. (Emphasis added.) (73)

And if the self was most authentically expressed when it was expressed sexually, it would not take long for people to need that expression to be protected and upheld politically. (This offers an explanation for something that has puzzled many observers. For example, in just over a decade, the political platform of the liberal Democratic candidate for president, Barack Obama, on a topic like gay marriage would be seen as retrograde and offensive, and is even to a certain extent repudiated by the man himself. This would appear to be a stark shift. Trueman’s work shows that the underlying intellectual work had already been done. In a word, public opinion on something like gay marriage turned so quickly because people’s intellectual assumptions had already removed every barrier to it.) If I were to condense Trueman’s argument, I might say that the self was individualized, then sexualized, then politicized.

Of course, this doesn’t explain everything. Trueman acknowledges the role technology has played in accomplishing all of this. But he successfully shows the intellectual foundations for this cultural moment are found in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Mary Wollstonecraft, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Freud.

The biggest strength of the book is its non-polemic quality. (Though this is belied by the fact that it is blurbed on the back cover by Ben Shapiro, the right-wing faux-intellectual.) Trueman does not seek to convince the reader of the badness of any of this. Of course, he is against it—that’s easy enough to tell. But Trueman is simply explaining why the Western world thinks the way it does.

In this way, it is doubly helpful. First, Trueman’s work really does explain much about our cultural milieu—including the ways it has seeped into the thought patterns of those who are, at least on the surface, contra mundum. (Take a look at the biggest hits on the Christian music charts and tell me that the expressive-individualized self does not have a foothold in the American church.) Second, Trueman’s work is a model for cultural engagement. There is a place for the jeremiad—much of the work of the prophets was in this mold. But if everyone’s pose toward the world is obviously antagonistic, our views end up in a cacophonous echo chamber, with none of our screeds actually convincing anybody. More of us—even if we are taking an oppositional stance—need to do the work of understanding. This book helps us to do so.