Slavery is the great American evil. It is our original sin—slavery and its aftermath has shaped the history of the United States in ways that nothing else has. It is right and good that we should reckon with this. Yet, slavery was also a global phenomenon. Many European nations took part in it. Africans populated huge swaths of North and South American because of it. It utterly reshaped the African continent. It is not only a stain on American history, but on human history as well.

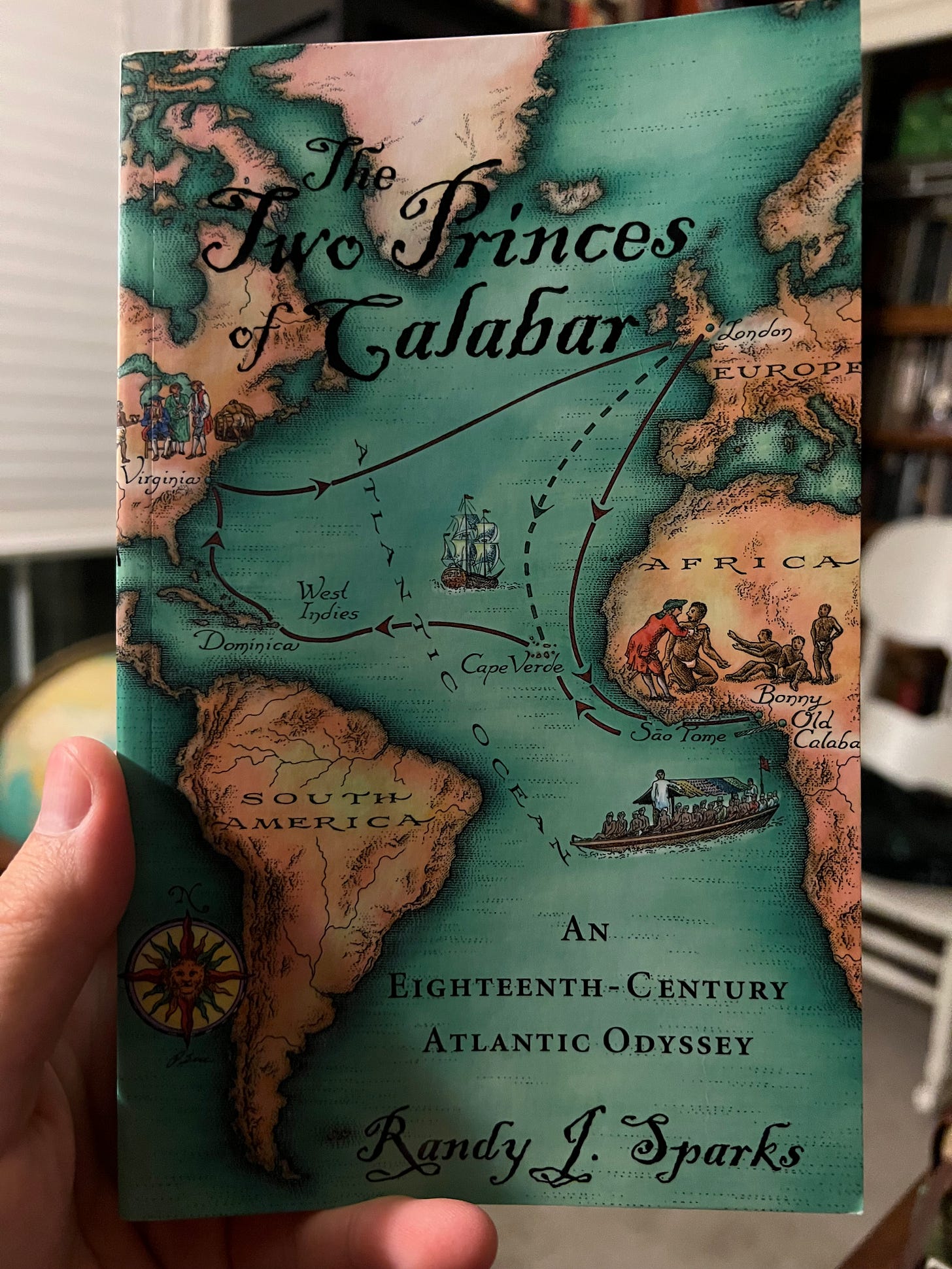

In The Two Princes of Calabar: An Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Odyssey (Harvard University Press), Randy J. Sparks tells the story of the international slave trade in a particularly intriguing fashion—through the eyes of two African men, who themselves were slave traders on the African continent, who were enslaved and taken on the Middle Passage before they were able to make it back home. Sparks ably shows how the interaction between men from Europe, the Americas, and Africa brought about a new, creolized culture, one that would shape the languages, practices, and identities of people from all three continents for decades to come. It is briskly written, uses primary sources in ingenious ways, and at a scant 147 pages of text is an ideal book to assign to introductory American history students.

For the sake of this blog, however, I was struck by the relationship the two African men at the heart of the book had with Charles Wesley, the great hymnodist of the First Great Awakening, and the brother of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. The close nature of their relationship is remarkable—in letters, they referred to “My Dear Charles” (132), and the Wesleys may have been involved in the their conversion to Christianity (111). And it’s at least plausible that they were involved in bringing the first Christian missionaries back to their African home in Old Calabar (135).

How does this Christianity fit with slavery? John Wesley himself opposed the American side in the fight for independence in part because injustice that American slaveholders inflicted on enslaved Africans far outweighed any injustice from Great Britain toward its American colonies. But Sparks makes a very interesting argument on this point, one that dovetails with Tom Holland’s in his excellent book Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. He writes, “The doctrine of Christian equality inherently challenged the racist underpinnings of the slave system, and enslaved converts often transferred doctrines of spiritual freedom and equality into the secular realm” (109).

This is not to say that Christians did not commit awful atrocities as the international slave trade and chattel slavery was being developed and put into practice, oftentimes even in the name of Christ. They most certainly did. And though, as Sparks points out, there was a great struggle over how Africans who converted to Christianity should be considered—could those who were spiritually free be rightly kept in physical chains?—well, American Christians eventually made their peace with this as well. As one of the Virginia slave codes put it, “WHEREAS some doubts have risen whether children that are slaves by birth, and by the charity and piety of their owners made partakers of the blessed sacrament of baptism, should by virtue of their baptism be made free; It is enacted and declared by this grand assembly, and the authority thereof, that the conferring of baptism doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom” (emphasis added). Simply put, for too many people, one’s spiritual status before God made no difference to one’s material status before man.

Still: Sparks, in drawing upon the work of historians David Brion Davis and Edmund Morgan, shows that this issue—the enslavement of Christian Africans—was apparently so thorny that it had to be addressed again and again in colonial legislation, revealing, as Davis put it, “a deep-seated doubt” as to whether such a thing was actually moral and permissible in a Christian society (109). Thus, it seems, these “Christian” slave traders and slaveholders had to “get over” their Christianity on this point, that their amenity to slavery was a kind of syncretism, a fusing of non-Christian human and economic desires with Christian doctrine.

What’s more, this issue was not only one for the white folks to consider. Enslaved folks considered this as well, and it was their faith in God that, in large part, motivated slave revolts for centuries to come. Wrote Sparks, “The role that Christianity played in inspiring slave revolts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries provides clear evidence that the link between Christian faith and freedom remained deeply embedded in African American Christianity” (110).

Despite the shortcomings of too many believers, Christianity utterly upends the justification for racism, slavery, white supremacism, and the like. This is the case not only theologically, as if it were some view that evolved with the times, but historically—and not only with regard to Gregory of Nyssa, the fourth-century church father who notably and bravely penned what is considered the “first truly ‘anti-slavery’ text of the patristic age.” Sparks shows how it is even true in the throes of the evil of the international slave trade.

May the doctrine of Christian equality continue to challenge evil in all its forms in our lives and in our world!