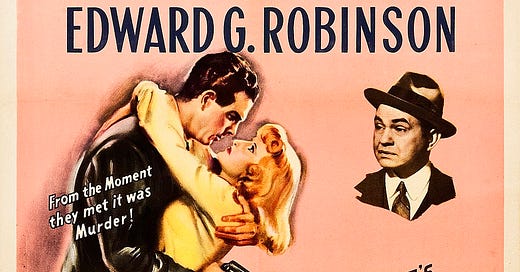

At a key moment in “Double Indemnity,” the 1944 film directed by Billy Wilder about an insurance salesman who schemes with a disgruntled wife to kill her husband and run off with his insurance payment (to disastrous consequences), Barbara Stanwyck, the wife, says to Fred MacMurray, the salesman, “I’m rotten to the heart.”

“Double Indemnity” is perhaps the prototypical example of a kind of film that has come to be known as film noir. The director Martin Scorsese has said, “Film noir was not a specific genre like gangster films, but a mood.” This is what film noir is—black-and-white films full of the contrasts of shadow and light, and the inexorable sense that these shadows will ultimately darken much more than the faces of the characters.

This is especially the case in “Double Indemnity.” MacMurray’s salesman is attracted to the sultry Stanwyck, and his lust for her leads him to agree to participate in her scheme for murder. Their collective greed, for the payout they would receive from her husband’s life insurance—sold to him by MacMurray’s character—drives them to commit this grave sin.

This would seem to mark them out as emotional beings, flitting this way and that based on whim and wherever their unchecked libido and green envy led them. But this is hardly the case. As the film critic Roger Ebert noted, these characters are cold, aloof, and cynical, and they remain so for the bulk of the film. It’s not just that their lives of sin never satisfied them—it almost seems as if they knew, all along, that their crime would never satisfy them. Then why did they do it?

In Augustine’s Confessions, he relays an account of him and some friends who steal some pears. Just like the characters in “Double Indemnity,” they did not steal in order to gain something they desired—he was not hungry, they were not particularly good pears that he could not find anywhere else. As he wrote, “My desire was to enjoy not what I sought by stealing but merely the excitement of thieving and the doing of what was wrong… our pleasure lay in doing what was not allowed” (29).

Why would human beings engage in such destructive behavior for no apparent reason, with no foreseeable gain in mind? Our contemporary culture would point to the need for therapy for such people, and indeed therapy often proves quite useful. But MacMurray and Stanwyck’s characters, their evil set aside, are not posed as particularly noteworthy people in this regard—MacMurray’s character carries on with his normal business throughout the picture. And neither was Augustine a particularly outrageous sinner as a youth—he was just like everyone else. And I suppose all of us have one story or another of doing some damaging thing out of some inner compulsion that we scarcely recognized ourselves.

The Christian explanation for this is that human beings are sinful. Sin is not simply something that is learned or picked up, though indeed in many ways it is. Sin is innate to who we are—we fail to live up to our own standards of moral uprightness, much less those of a holy deity.

And so, “Double Indemnity” points the mirror back at us. For we, too, are rotten to the heart. As it says in Jeremiah 17:9, “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?” MacMurray and Stanwyck needed a way out, a way to cleanse the rottenness from their hearts, just as we do. In film noir, there is no way out. But this only points us all the more to Jesus, who cleanses the rottenness from our hearts by enduring the combined sinful rot of all of humanity on the cross. “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21).